New findings on benefits of “biofactors” in food

Can what we eat help fix what ails us? Research increasingly suggests the answer is “yes.” Many foods contain biofactors — biologically active compounds — that may prevent and treat illnesses including asthma, diabetes and heart disease, according to new studies from the UC Davis Center for Health and Nutrition Research (CHNR).

The upcoming July-September California Agriculture journal (to be posted by July 11) reports UC research into plant compounds (phytochemicals) that can help prevent or treat disease. The findings stem from pilot projects at the center, as well as other UC research. Articles focus on how micronutrients, biofactors and phytochemicals (plant compounds) can help reduce the risk of chronic diseases.

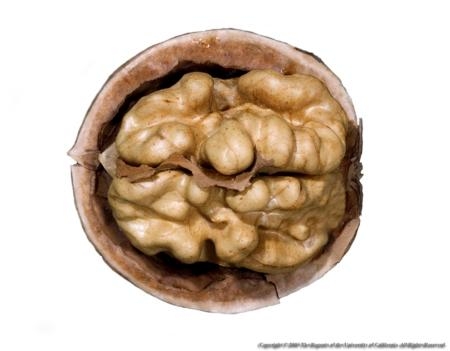

Biofactors are compounds in our food that affect us at the biochemical level and may ultimately benefit our health. For example, the omega-3 fatty acids in foods such as walnuts, flax seeds, kale and salmon may protect against a range of diseases associated with inflammation, including asthma and the hypertension-related inflammation that can damage kidneys. CHNR research suggests that omega-3 fatty acids could reduce asthma symptoms as well as kidney damage.

Phytochemicals and health. Epidemiological studies link particular diets to less risk of chronic diseases. Notably, the traditional Mediterranean diet — mostly vegetables, fruits and whole grains, with moderate amounts of nuts, olive oil and red wine — is associated with lower rates of heart disease, cancer, and Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases. However, it has yet to be firmly established that specific phytochemicals in our diets can protect against diseases. Nutritionists therefore advise eating a wide variety of plant-based foods rather than taking supplements.

That said, a number of phytochemicals do show promise in protecting against and even treating chronic diseases. For example, research shows that soybeans contain estrogen-like compounds called isoflavones that may protect against heart disease, and that compounds in olive oil and red wine may protect against heart disease and diabetes.

Mitochondrial nutrients and aging. The Mediterranean diet is rich in plant compounds that boost mitochondria (organelles in our cells that convert glucose and other nutrients into energy) and so are known as mitochondrial nutrients. When mitochondria are scarce or have genetic defects that keep them from working properly, this can generate toxic metabolites and damaging free radicals.

“Mitochondria are central to aging,” says UC Irvine aging expert Edward Sharman. “Improving their function may modulate or delay the onset of diseases related to aging, such as type 2 diabetes and age-related macular degeneration.” Mitochondrial dysfunction also plays a key role in chronic illnesses such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes and inflammatory diseases such as arthritis.

One of the most promising mitochondrial nutrients is hydroxytyrosol, which is abundant in the extra-virgin olive oil that provides most of the fat in the traditional Mediterranean diet. Moreover, the red wine that is integral to the Mediterranean diet also induces the body to produce more hydroxytyrosol.

A new essential nutrient? Another promising mitochondrial nutrient is pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ), which was first found in nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria and is now known to be ubiquitous.

“We’re exposed to PQQ all the time at low levels,” says CHNR co-director Robert Rucker, a UC Davis nutrition professor. “It can be derived from amino acids found in stellar dust, and stellar dust is what the earth is made of.”

While Escherichia coli and other common gut bacteria do not make PQQ, the soil bacteria provide it to the plants in our diet. Good sources include fermented soybeans, wine, tea and cocoa.

Animal studies show that PQQ affects health markedly. Rucker and his colleagues found that depriving rats of PQQ compromised their immune systems, and retarded their growth and reproductive rates. In contrast, restoring PQQ to their diets reversed these effects and returned them to good health. Moreover, PQQ stimulated nerve growth and counteracted aging in cultured cells.

Rucker and his colleagues found that, like hydroxytyrosol, PQQ increases the number of mitochondria in cells. “It’s also an extremely good antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agent,” he says.

Personalized medicine. Understanding what biofactors do in our bodies could ultimately lead to personalized medicine, where nutrition-based treatments are tailored to the particulars of each person’s biochemistry. This individual variation at the biochemical level may help explain the inconsistent outcomes of research on omega-3 fatty acids and inflammation.

“The studies are mixed,” says UC Davis pulmonologist Nicolas Kenyon. “Some have shown little effect and others have shown that omega-3 fatty acids can reduce arthritis and inflammation in blood vessels.”

This genotyping is targeted to DNA sequences associated with asthma and so is not comprehensive.

“Some people are nervous about genome-wide analysis, which is scary because none of us is perfect,” Kenyon says. “But people are more interested when the focus is specific screening that could increase their chances of treatment.”

Posted by Janny on March 16, 2013 at 12:23 AM